Did George Mayes Purchase the Cuchara Camps Land in 1906, 1907, or 1910? Although often described in local histories as a direct 1906 purchase from W. J. Gould, county records reveal a more complex transaction. Let’s unravel the mystery.

Unfortunately, county records rarely cooperate with tidy stories.

What emerges instead is not a contradiction of Mayes’s role or vision, but a far more interesting and typical early-twentieth-century land transaction. A transaction that unfolded in stages, involved private financing, and left behind a paper trail capable of confusing even the most determined historian armed with strong coffee and good intentions.(1)

Let’s untangle it.

The Source of the Confusion

The difficulty begins with a reasonable assumption: if George Mayes was developing Cuchara Camps by 1907, surely he must have owned the land by then. Local histories and modern articles understandably collapsed the timeline, rounding the story to a neat 1906 purchase and moving on to more scenic matters like cabins, dining halls, and summer guests.

But land ownership is not always so accommodating. In the early 1900s, especially in rural Colorado, it was common for property to change hands through privately financed, multi-year arrangements rather than a single cash-and-keys exchange.(2) That is exactly what happened here.

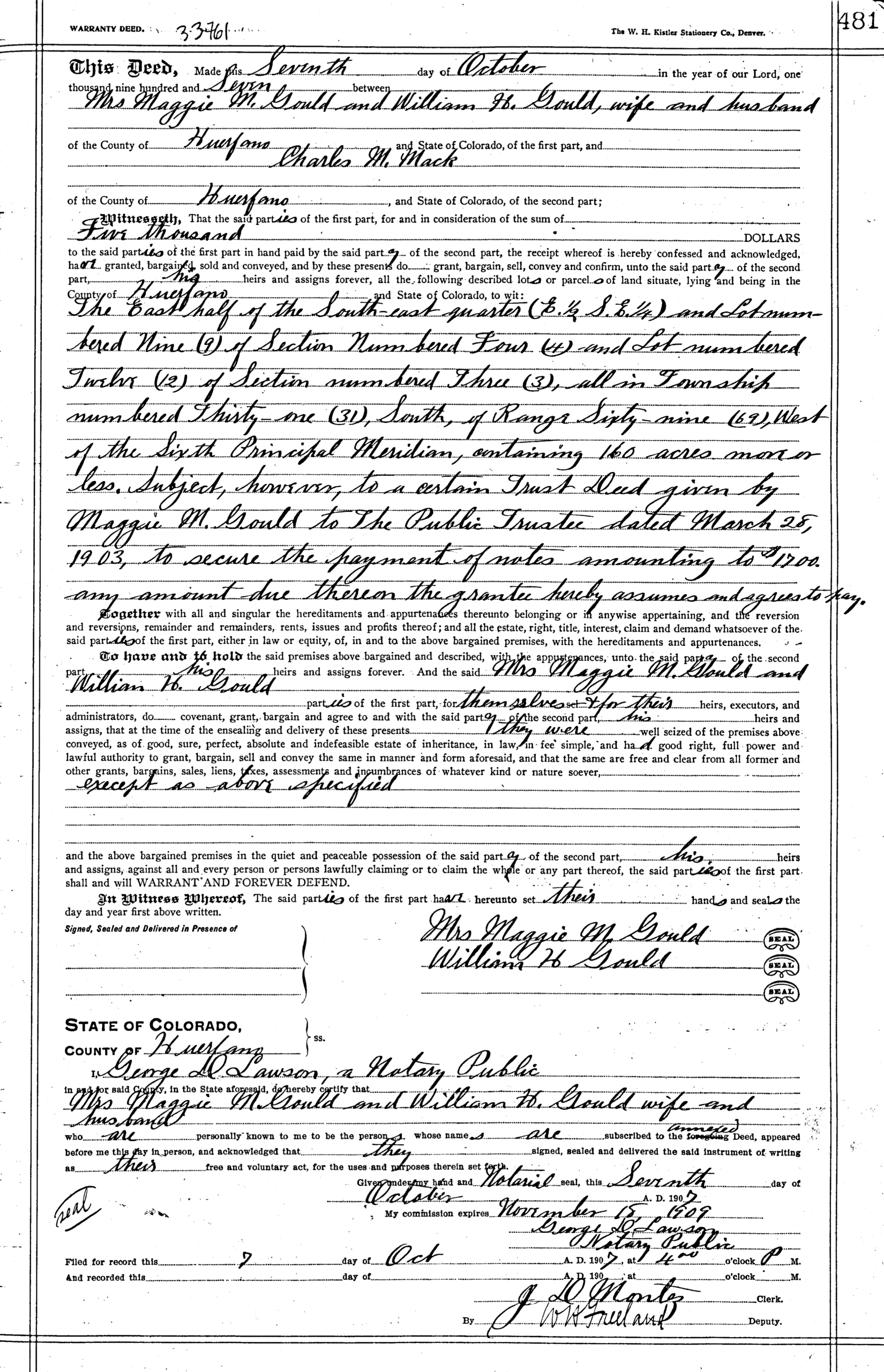

Step One: The Ranch Leaves the Goulds (1907)

The first documented ownership change does not place George Mayes on the deed at all. In October 1907, William J. Gould and his wife conveyed the former Gould Ranch to Charles M. Mack by warranty deed.(3)

Mack was not a developer, a resort operator, or a colorful mountain entrepreneur. He was, however, well positioned to function as a private financier, a role far more common in this era than modern readers might expect.

In modern terms, the arrangement would be familiar to anyone who has ever bought a home with a mortgage. Mayes moved onto the land, invested heavily in improvements, and began building his vision while legal title remained with the financier as security. Possession and responsibility came first; ownership on paper followed later.

At this point, the land legally belonged to Mack, not Mayes.

Step Two: Mayes Enters the Picture (Also 1907)

Only days after Mack acquired title, George Mayes appears in the record, but not as an owner. Instead, contemporaneous mortgage and deed of trust filings document Mayes’s financial obligations under a privately financed purchase arrangement covering the same land, described by Public Land Survey System (PLSS) terms as Sections 3 and 4, Township 31 South, Range 69 West.(4) Together, these documents make one thing clear: Mayes had possession and responsibility

In plain English, this means Mayes was allowed to move onto the land, improve it, and begin development under a seller-financed arrangement, while Mack retained title as security. This was not unusual. In fact, it was often considered safer than dealing with distant banks that viewed mountain valleys with skepticism, forests as fire hazards, and snowdrifts with alarm.

Thus, by 1907, Mayes could legitimately begin building Cuchara Camps without yet being the legal owner.

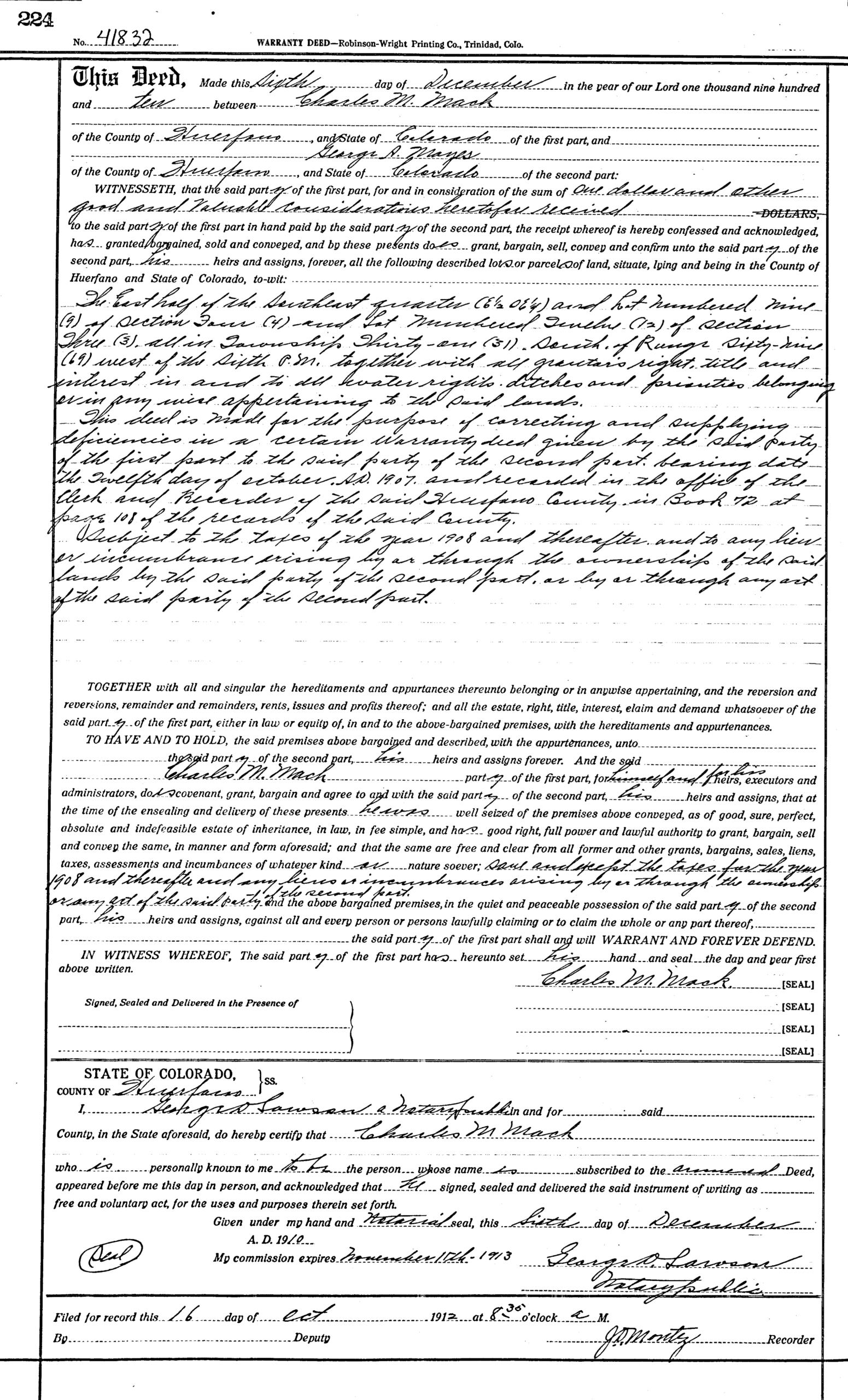

Step Three: The Deed That Settles the Question (1910)

The final and decisive document arrived three years later. On December 6, 1910, Charles M. Mack executed a warranty deed conveying full legal title to George A. Mayes, completing the transaction.(5) Only at this point did ownership and possession finally align on paper.

From that date forward, there is no ambiguity: Mayes owned the land outright.

In modern terms, this was the moment the mortgage was fully paid. The financier released his interest, the paperwork caught up with years of on-the-ground reality, and the deed was finally recorded in the builder’s name. On December 6, 1910, Charles M. Mack executed a warranty deed conveying full legal title to George A. Mayes. From that date forward, there was no ambiguity: ownership and possession were one and the same.

So… Which Date Is “Right”?

The answer depends on what one means by purchase.

- 1906 reflects the beginning of negotiations and Mayes’s association with the property, but no surviving deed supports a completed transfer that year.

- 1907 marks the moment Mayes gained access, control, and the ability to develop the land while legal title remained with Mack.

- 1910 is the date ownership was formally and finally conveyed by warranty deed.

Each date tells a true part of the story, but only together do they tell the whole one.

Good News and Why This Matters

Understanding this sequence changes the timeline but not the significance of Mayes’s work. This clarification does not diminish George Mayes’s role. If anything, it highlights his commitment. Mayes began developing Cuchara Camps before holding legal title, a decision that required confidence, resources, and no small measure of optimism that would define the resort itself.

It also reminds us that history often unfolds less like a postcard and more like a filing cabinet. The story was never wrong so much as compressed, simplified over time for convenience. County records simply invite us to slow down and enjoy the longer version. And, truth be told, if early-twentieth-century land deals were easy to understand, historians would have far less fun.

Finally, this story highlights a common thread between the development of Cuchara Camps and Pinehaven. Beneath the deeds, dates, and legal descriptions, we see that George Mayes was not so different from Steve Peirotti, the founder of the Pinehaven Cabin community. Both men were entrepreneurs in the truest sense of the word. They were willing to borrow against tomorrow in order to build something they believed in today. Neither waited until the land was fully paid for or the path was perfectly clear. They stepped forward anyway.

They were bound by a common temperament: imagination strong enough to see a future others could not yet picture, courage enough to accept real financial risk, and stamina to keep working long after easier men might have quit. They understood that land is never just acreage. It is possibility. And they trusted that if they stewarded it well, others would someday come to love it too.(6)

Footnote

Parenthetical numbers in the text (e.g., 5) correspond to the sequentially numbered citations listed below.

1. Gene Roncone, “Untangling the Confusion About Cuchara Camps Land Purchase” (unpublished research memorandum, Journal 79 supporting documentation, Huerfano County, CO, 2025), PDF available at http://www.agspe.org/Untangling_Confusion_About_Cuchara_Camps_Land_Purchase.pdf

2. Seller-financed land transactions often involving retained title, deeds of trust, and delayed conveyance were common in rural Colorado during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, particularly where access to institutional banking was limited.

3. Warranty Deed, William J. Gould and wife to Charles M. Mack, recorded October 1907, Huerfano County Clerk and Recorder, legal description: Sections 3 and 4, Township 31 South, Range 69 West (Document Identifier: 033761 and Book/Page: GENERAL-66-481).

4. Mortgage, Charles M. Mack to George A. Mayes, recorded October 12, 1907, Huerfano County Clerk and Recorder, Document No. 034402, Book GENERAL-72-108; and Deed of Trust, George A. Mayes to Charles M. Mack, recorded October 12, 1907, Document No. 034082, Book GENERAL-72-12, covering land described as Sections 3 and 4, Township 31 South, Range 69 West.

5. Warranty Deed, Charles M. Mack to George A. Mayes, recorded December 6, 1910, Huerfano County Clerk and Recorder (Document Identifier: 041832 and Book/Page: GENERAL-83-224).

6. Author’s note: In preparing this article, the author used AI-assisted tools for research support, proofreading, fact-checking, and stylistic refinement. The narrative, analysis, and historical interpretations are the author’s own, and responsibility for accuracy rests solely with the author. The blog’s research methodology statement is available at: https://cabininthepinescuchara.blogspot.com/2019/03/methodology-sources-and-use-of-research.html